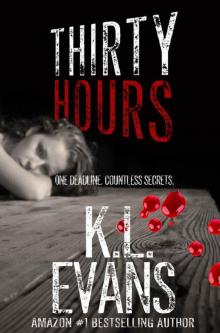

Thirty Hours: a semi memoir of psychosis and love Read online

Thirty Hours

K.L. Evans

Thirty Hours

K.L. Evans

Copyright © 2018, K. L. Evans. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author.

This is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents and dialogues in this book are of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is completely coincidental.

Cover Art by Q Design

Interior Formatting by Sarah Bale

Manufactured in the USA

Contents

Hour One

Hour Two

Hour Three

Hour Four

Hour Five

Hour Six

Hour Seven

Hour Eight

Hour Nine

Hour Ten

Hour Eleven

Hour Twelve

Hour Thirteen

Hour Fourteen

Hour Fifteen

Hour Sixteen

Hour Seventeen

Hour Eighteen

Hour Nineteen

Hour Twenty

Hour Twenty-One

Hour Twenty-Two

Hour Twenty-Three

Hour Twenty-Four

Hour Twenty-Five

Hour Twenty-Six

Hour Twenty-Seven

Hour Twenty-Eight

Hour Twenty-Nine

Hour Thirty

3:59 AM

Aftermath

Dear Reader:

If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, please take advantage of one of the following resources:

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Also by K.L. Evans

For You.

One who is trapped within himself will do anything to be free.

—Unknown

Hour One

Okay, listen up.

Time is all we’ve got left right now and I’m not the kind of person who wastes time. I realize you are really committed to this little plan of yours, but I don’t think you have enough information to realize it’s a horrible idea, so I’m going to help you try again.

Got it?

You know… truthfully… time is all any of us have. At the moment we’re born, we’re given a name; we’re immersed in a culture that may include a religion or a set of beliefs determined by parents or guardians. A doc slaps you with a gender and doesn’t have the decency to ask your opinion about it. The state provides us with an identification number. All these things are given to us by various entities, but the one thing we truly, intrinsically possess is time.

What we choose to do with our time determines the course of our lives. We spend our lives trading our time for things. We trade it for relationships, an education, a paycheck, hobbies—whatever we do, the currency with which we barter for everything is our time. What we choose to purchase with it shapes and defines us.

None of us know how much time we ultimately have, but I digress because none of that matters right now, and I’m wasting time, and I don’t waste time.

Back to us.

Time is all we have. You and me. Right now. We have some time and I don’t know how much. What I choose to do with this undetermined amount of time could determine the course of the rest of your life and mine.

And do I have the temerity to believe I wield that kind of power?

Well… yes.

But desperation will do that to a person, won't it?

And desperation is why I’m not going to hope right now. I’m just going to talk.

You need to know I want you and I want you here. With me.

There are so many reasons for you to stay here and be here. I don’t think I did a good job communicating that to you before now, hence your obvious insistence upon following through with your plan to leave me like this. You need to know my side of the story, so I’m going to tell you everything I know about us and everything I know about you.

You.

That odd young woman. That’s how everyone referred to you.

Strange girl. Local nuisance. The weird one who does all that crazy stuff, everyone kept saying to me, dumb stuff that keeps getting her arrested.

No, she never does anything really bad. Just disturbing the peace.

She’s a very sweet lady. She doesn’t like to talk much though.

She’s so thin. I wish someone would give her a sandwich or something.

She’s troubled.

I can’t tell if she’s overwhelmed or if she’s just given up.

The first time I saw you was at the fountain near the corner of Young and South Record Street. The mid-May sun was warm and dry on my skin as I waited to cross the street and the time on my watch read 12:51. And then, from behind me, like a chickadee raising its tiny, little ruckus:

“And I-I-I-I-I wanna knooow! Have you evaaaa seeeen th’raaaain?”

So of course I had to turn and look.

It isn’t every day you see a naked woman splashing around in a fountain in the middle of Dallas, laughing and singing golden oldies. The sight seared my mind and my eyes like it was the first time I’d looked directly at the sun.

“Comin’ dooown on a suuuunny day?”

In my strenuous effort to keep my gaze from darting to your breasts—forgive me for being a guy, but I did try not to look—I focused on your eyes and you stared right back at me. And with that, your strange behavior and nudity faded into the blinding sunlight and all I saw was your eyes; eyes that glittered like the water droplets you were kicking into the air and looked like they belonged on a peculiar mash-up of the comedy and tragedy masks.

A squad car siren chirped twice, jolting us out of the mutually locked stare, as the cops pulled up and the traffic light changed. I crossed the street and strolled into the Dallas Morning News offices, wiping the smirk off my face and filing you away in the back of my brain just in case I’d need you later.

I didn’t need you right then because I already had three subjects for works-in-progress:

1. Shonda Sterling: Incarcerated. Charged as accomplice to boyfriend (busted with $25K worth of coke).

2. Isabel Perez: Undocumented 17 y/o valedictorian, Red Oak HS. Announced lack of citizenship during commencement speech.

3. George Traynor: Widower. 7 y/o son, Michael is dying of osteosarcoma.

My plate was already full. I wouldn’t need you for at least another three months.

Horseless Lady Godiva from the fountain, I hastily typed into my phone as I waited for the elevator. Arrested. Follow up w/DPD for name and charge.

I slipped the phone in my pocket and forgot to follow up with the police department and forgot about you for the most part until the second time I saw you.

The second time I saw you was a month later. Michael Traynor passed away the morning of June 20 and after George had obliged me with a heart-lacerating and abbreviated interview that evening, I needed a drink. The closest pub in Fort Worth was on Calhoun and, absently peering over the rim of my glass, lo and behold.

Hunched over the bar, pen in hand, a beer and a shot of whiskey within arm’s length, hair draping over your shoulders, you sat at the bar while furiously scribbling on a newspaper. I knew it was you because of that hair; your cascading, stick-straight, black-coffee hair.

I also knew it was you because—and my apologies to women everywhere for commenting on your weight, but seriously—you are so thin. Thin like that isn’t

common in Fort Worth or Dallas. Women here are usually either in perfect physical shape because of money and personal trainers and surgery, or comfortably round because of happiness and life. There I go again, talking about women’s weight, but I swear to God I have a point and my point is this:

Nine times out of ten, women who are thin like you are either homeless or on drugs—but you didn’t appear to be either of those things. You just looked different. Maybe it’s the reporter in me that made me think your being that thin and not looking like a homeless junkie had a story attached to it. And maybe it’s the reporter in me that makes me believe I was right.

That time I had an immediate compulsion to approach you. I was two inches off my chair when the bells on the front door jingled and a lanky man with a high-and-tight haircut sauntered into the pub and dropped himself onto the stool next to you.

He appeared to be about thirty-five; at least ten years older than you. He wore a wedding band and you didn’t. Your body language was that of two friends; laughter and swearing; fist bumping and clinking shot glasses together before shooting liquor. However, I decided this gentleman—and believe me, I use the term loosely—wasn’t necessarily your friend when you’d hunch over the newspaper to scribble and he’d draw his gaze from one end of you to the other.

That and when he let you stagger out of the bar two hours later, swinging your keyring in circles around your index finger.

I almost got up to stop you so I could call a cab, but I didn’t and I couldn’t pinpoint why.

And then of course I wondered if that was the last time I’d ever see you, as I considered the possibility of you killing yourself in a wreck during your drive home—none of which ended up being the case because I did see you again. Exactly two months later.

The third time I saw you was on a Friday at a pharmacy in Grand Prairie. I had decided to start my weekend early and you were studying a refrigerated case, chewing the insides of your mouth in a way that caused your lips to pucker. I’ll admit I stared for longer than necessary. I can admit that now. Now that it probably doesn’t matter.

Anyway.

The Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex amasses more than seven million people and there you were again. It had to be fate—even though I don’t believe in fate.

I opened my mouth to say something to you, but wasn’t able to put voice to my words before my phone rang.

“McCollum!” my editor barked. “Where the hell are you?”

“Uh, I’m… uh,” I faltered and you flung the door open, grabbed a drink, and skipped away down one of the aisles, “just checking into a lead.”

I wasn’t checking into a lead—at least I didn’t realize I was at that point—and you were leaving.

“What’s the lead?” he demanded, and I noticed paper bags of prescriptions in your hand.

“Early twenties female,” I blurted on sheer reflex. “She got arrested for skinny dipping in the fountain across the street from the newsroom.”

“And?” he barked again, and I could practically feel him breathing down my neck; a famished dog jonesing for a bloody steak just out of his reach.

“And she was singing,” I added, grasping at straws, grabbing a Coke, and slinking toward the register. I had nothing for him and he probably knew it. “You had to see it. It was like modern-day Lady Godiva—”

“AND? How is that newsworthy? Your column isn’t an excuse to sniff out a piece of ass, McCollum, it’s a—”

“It’s a human interest column, I know. It’s not supposed to be newsworthy. It’s supposed to be interesting.” I was being a little too ballsy for my position, but I did have a point and he should’ve seen it. For good measure, I turned my back to the register, ducked below the shelves, and lowered my voice. “And I think she might be some kind of nudist exhibitionist. Or she’s a hooker. Or she’s homeless. I don’t know yet. But something’s there.”

Straight-up fabrications, but I’d been caught skipping work and had no other leads and only a feeling. I couldn’t explain the feeling, so I needed the fabrications to get him off my ass.

“Whatever, McCollum,” he relented. “You can play hooky today if you want, but if I don’t have a premise and an outline next week you’re going to be chained to your desk writing the Metro Blotter until you’re too senile to find the space bar.”

“Well… shit,” I mumbled, slipping the phone into my pocket. My work was cut out for me and, in retrospect, my fate was sealed because had I not received that phone call, this story would’ve ended right there in the pharmacy.

The cashier rang up your sugar-free Red Bull and the three prescriptions. I squinted at the labels, attempting to glean your name and what the medications were, but the cashier stuffed everything into a plastic bag before the letters registered as words. Then you were out the door.

I tossed a five on the counter and darted outside, scanning the cars in the parking lot for you. In the far corner of the lot, parked in the most conspicuously inconspicuous location available, you sat in a beat-up black Pontiac, head tilted down, while your hair fell in a dark curtain around your face.

You sat like that for a moment—not long enough for me to figure out how to approach you in a non-threatening way—and then backed up the car and pulled out of the parking lot. So, naturally, there was only one thing for me to do.

I followed you westbound on I-30, away from Grand Prairie, through Arlington, through Fort Worth, until you exited and pulled into a strip center. Since this step in researching a lead is little more than stalking, I circled the block before parking at an opposite end of the lot so you wouldn’t catch on to me following you.

The strip center consisted of a laundromat, a dollar store, a vacant storefront, and a really seedy-looking bar. The dollar store was closed and only an elderly woman sat in the laundromat, which left just one option.

As I crossed the threshold, the bar blasted me with frigid air from an overworked HVAC system and Johnny Cash’s I Walk the Line crackling from a juke box on its last leg. Dank, musty darkness filled the atmosphere and once my pupils had stretched to the diameter of dinner plates, I was able to see the sparse gathering of older, blue collar patrons milling about and you seated at the bar.

Once again, your only companions were a newspaper, a pen, a beer, and a shot. Once again, you were scribbling furiously, pausing only to shoot whiskey and chase it with beer. And once again, I was compelled to approach you, although that time it was more a result of wanting to keep my job. Conveniently, the neighboring empty stool was close enough that I didn’t have to be any creepier than I already felt by sliding it closer to you.

I sat. I ordered a Lone Star longneck and slouched in my meticulously pressed Kenneth Cole trousers in an effort to fit in with the salt-of-the-earth types, all of whom I was positive were side-eyeing me. I sipped it, silently applauding myself for not gagging or recoiling too obviously at the fact I set my sleeve in a small puddle stale beer. But mostly I watched you.

You were skimming over the lines of text and circling letters, eyes narrowed and brow furrowed with intense focus. Page after page after page. You went through two beers and two shots as you skimmed and circled, and I choked down a beer and a cheap shot as I watched you. You didn’t even look up.

“Yes I’ll admit that I’m a fool for you,” some roughneck was crooning in rich baritone next to the jukebox. “Because you’re mine, I walk the line.”

And the first thing I ever said to you took the form of a question as I inclined my head and noticed the delicate slope of your nose. “Is that some kind of puzzle?”

You glanced up at me through a pair of striking gray eyes that appeared blue in the low light of the bar, and then looked back at the paper. “Not really.”

“So what are you doing?”

You looked at me again and a bemused smile tugged the corners of your mouth. “You’re nosy.”

“I can’t really deny that.”

You kept smiling and your smile was cute enough to make anyone sm

ile, me included—even though smiling at you was not why I was there.

“Are you looking for hidden messages in the articles?”

“No. It’s just a mindless activity I do at bars. It makes me look like I’m doing something important so men are less likely to hit on me.”

“Well I’m not hitting on you, so you don’t have to worry about that.”

“Good to know.” You were amused and snarky, and I had to remind myself that, no. No, I’m really not hitting on you.

“Because you’re mine,” the roughneck was concluding from across the room, “I walk the line.”

“Have you ever been to the fountain at the corner of Young and South Record Street in Dallas?” I asked, which, knowing we’d both know the context, really sounded like hitting on you, but I told myself I was still just researching a lead.

You lifted your head again and shot me a look that was something like who the hell are you, but that didn’t deter me. “Are you sure you’re not hitting on me?”

“Positive.”

“But you saw me in the fountain and just happened to find me all the way over here all these months later.”

“Yes.”

“So maybe you’re just stalking me.”

“Not in the way you’re thinking.”

You scrunched up your face. “But you are stalking me.”

“I don’t really like the word stalking. Not in this context.”

Thirty Hours: a semi memoir of psychosis and love

Thirty Hours: a semi memoir of psychosis and love